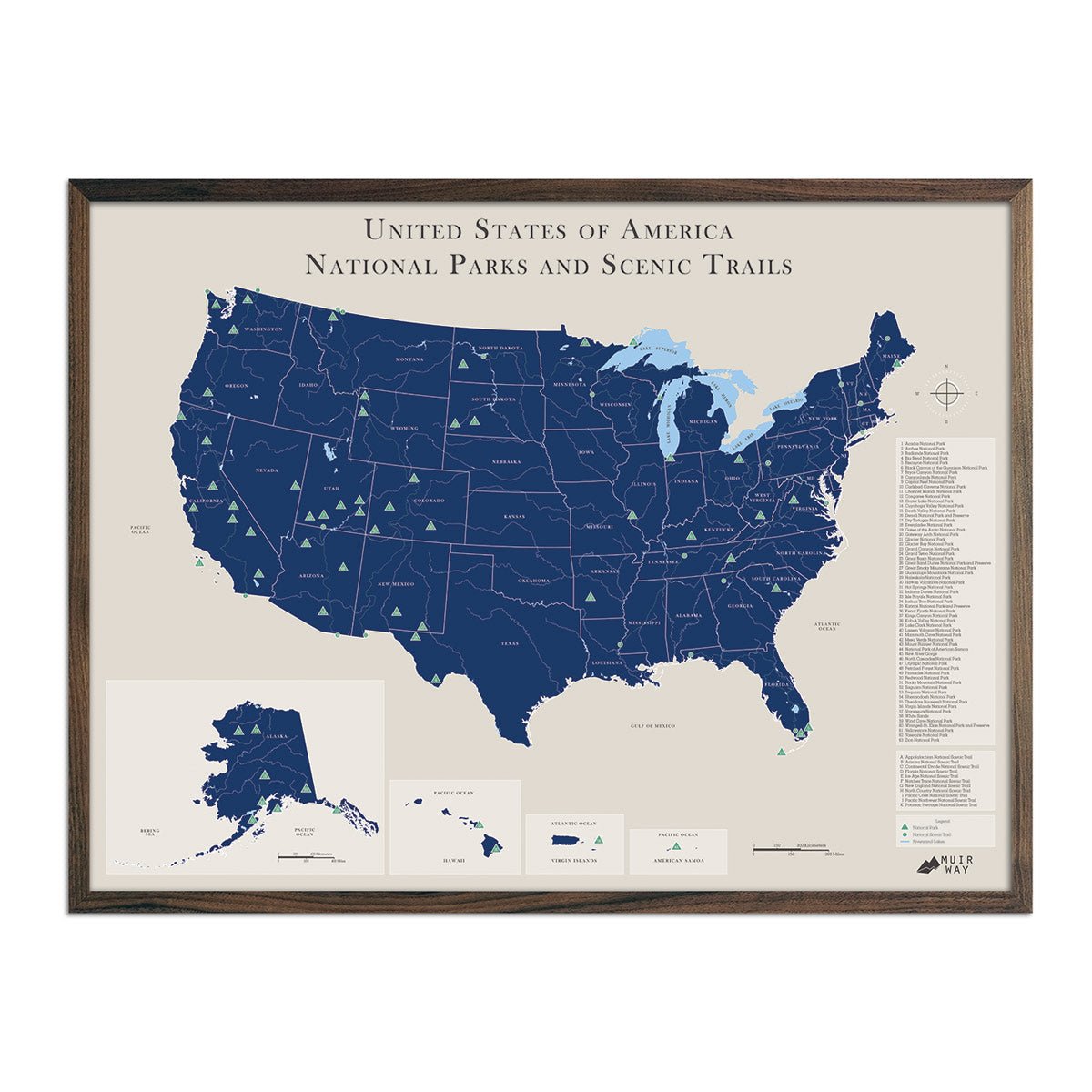

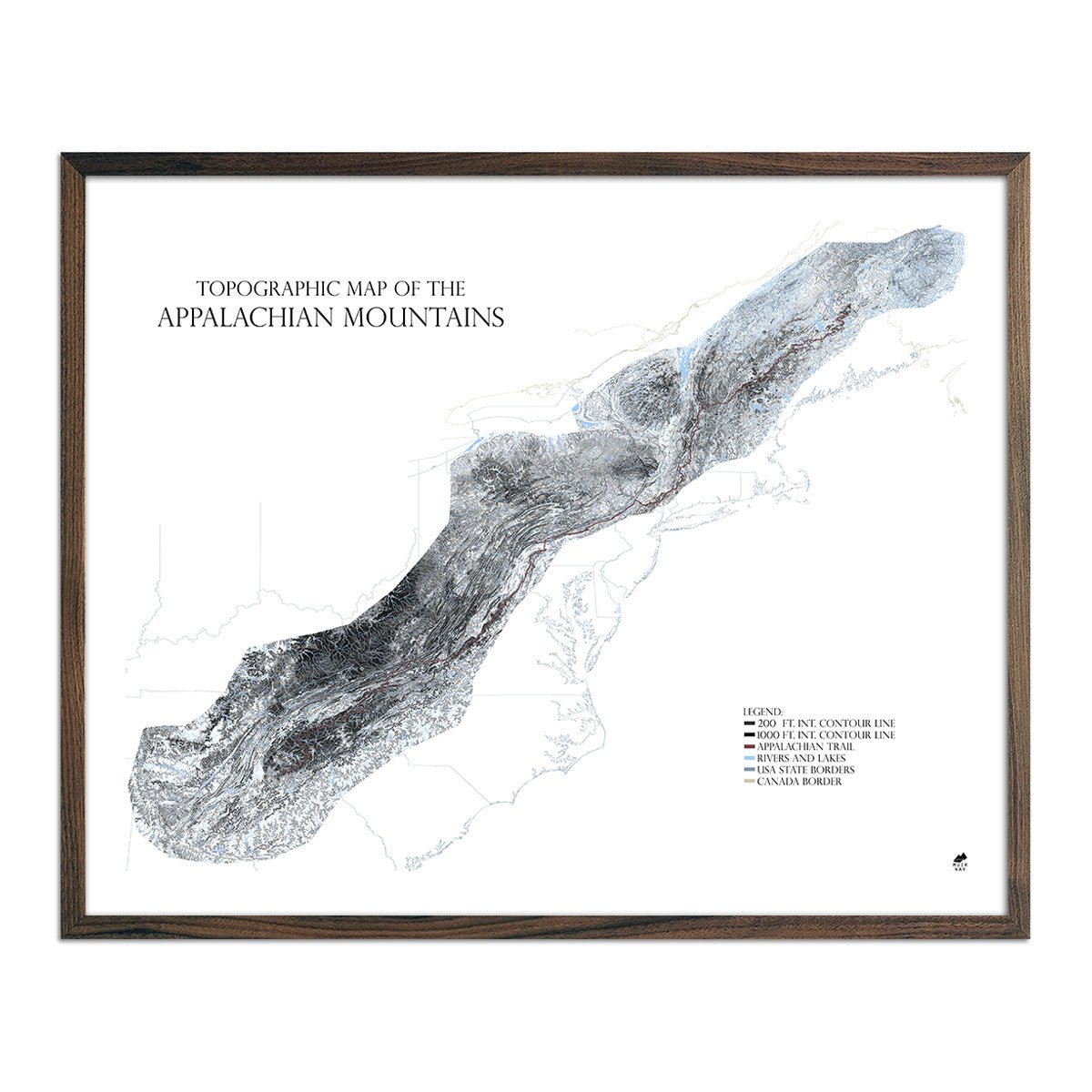

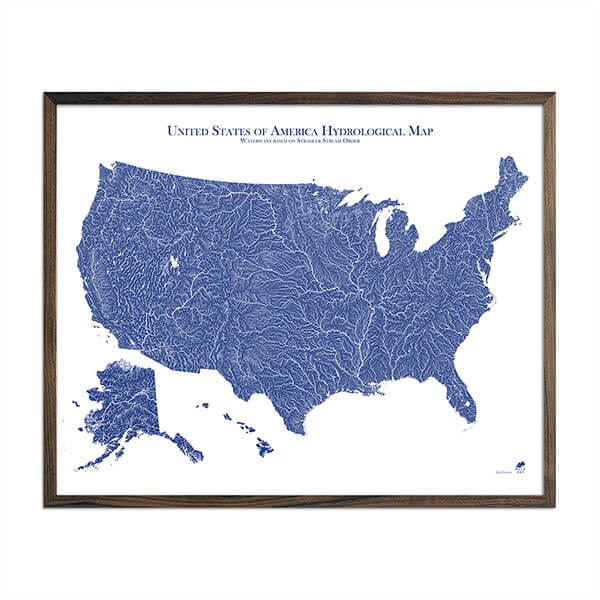

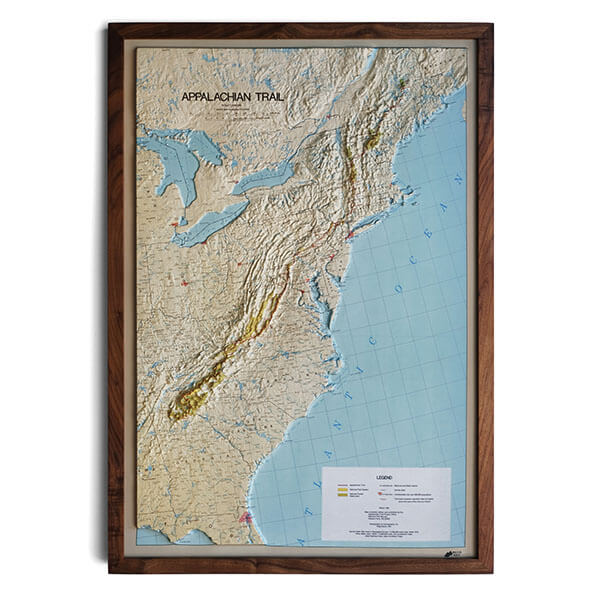

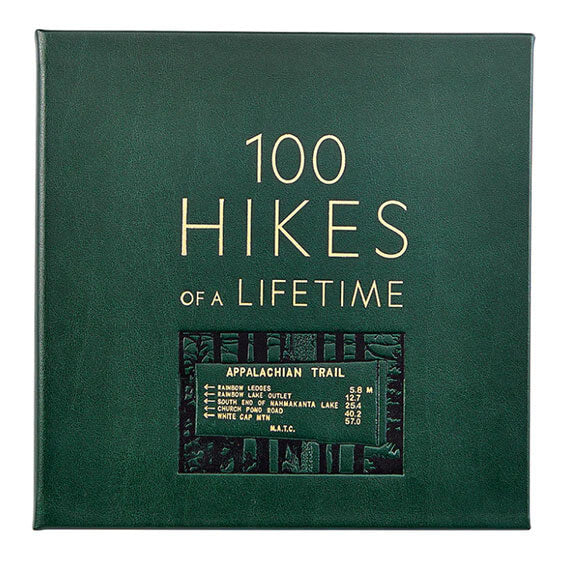

Extending all the way from Maine to Georgia, the Appalachian Trail is the longest hiking-only footpath in the world. The trail, with more than 2,000 miles spanning 14 states, sees approximately 3,000,000 visitors each year.

Today, the trail is managed by the National Park Service, US Forest Service, Appalachian Trail Conservancy, state agencies and countless volunteers, but that hasn’t always been the case.

In 1921, the idea for the trail was conceived by a single person: regional planner Benton MacKaye. As a forester, MacKaye lived by the philosophy that land should be preserved for both recreational and conservation purposes, a concept he called “Geotechnics.” With this idea in mind, Benton, along with a group of private citizens and supporters, organized the Appalachian Trail Conference (ATC). Together, they hoped to realize MacKaye’s vision of creating a footpath that ran from New England to the southern Appalachian Mountains.

Although enthusiastic from the outset, the group failed to make much progress over the course of five years. In that time, they managed to connect some existing paths and create a few new ones in New York but were far from finishing the hiking trail MacKaye originally envisioned.

Moving Towards Completion

The 1920s saw a change of leadership in the ATC when retired Connecticut judge, Arthur Perkins, took the reins from MacKaye. Perkins’ work on the trail led him to the Potomac Appalachian Trail Club (PATC), a group that was already making great progress on the Trail in West Virginia.

The PATC is where Perkins would meet retired federal admiralty lawyer, Myron H. Avery who would eventually succeed Perkins as head of the ATC and, with plenty of support and momentum behind him, led the way to the Trail’s completion in 1937.

The Push for Federal Protection

Even though the footpath was complete, the A.T. project wouldn’t truly be finished until the Trail received federal protection – an integral part of MacKaye’s original vision. Recognizing the importance of preservation, the National Park Service had taken measures to gain federal protection long before the footpath was complete.

But those plans were temporarily placed on hold due to a series of events that were unfolding at the time. First, in 1938, a hurricane ripped through New England leaving portions of the Trail in disrepair. Soon after, volunteers and ATC members were preparing for what would become World War II with many being called to active duty.

The damage from the hurricane and lack of maintenance over the years led many to believe the A.T. was no longer passable from Maine to Georgia. But, three years after the end of WWII, Earl V. Shaffer was in fact able to make his way through the 2,000-mile journey, a feat that breathed new life into the preservation, protection and conservation plans the Trail needed to survive.

The Path to Protection & Conservation

Following the death of Avery in 1951, two leaders, Murray Stevens and Stanley Murray, would continue the push for federal protection. Thanks to their efforts, the ATC saw membership numbers jump from a few hundred to more than 10,000 during the 1950s and 60s. This period of great growth helped fuel several legislation initiatives that would eventually grant federal ownership of the land the A.T. occupied – a move that would ensure its protection for generations of hikers and backpackers.

Their efforts paid off in 1968 when President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the National Trails System Act into law, making the A.T. the first national scenic trail. This designation finally gave the Trail federal protection under the National Park System – 47 years after MacKaye first made his idea public.

Appalachian Trail Land Acquisition

The National Trails System Act called for state and federal purchase of land that contained portions of the footpath. To help with the new phase of protection plans, the ATC hired its first employee and moved their headquarters to Harpers Ferry, West Virginia. This move allowed them to be nearer to the Trail and work more closely with agencies that would help with land purchase.

While the USDA Forest Service was quick to enter the land purchasing phase, the National Park Service (NPS) continually stalled acquisition efforts on the 40% of the Trail they were responsible for. The ATC fought back to secure the much needed protection the Trail deserved. Congress agreed and directed the NPS to set aside a budget specifically for A.T. land acquisition. It was also under this new plan that the National Park Service gave ATC the right and responsibility to manage the Trail.

Remaining Miles

By 1986, only 100 miles or so were left of the original 2,190-mile footpath. With completion in sight, it became top priority to acquire the last remaining miles. However, many years of land negotiations remained, the largest being a protected route over Maine’s Saddleback Mountain. Finally, the last stretch of land would be formally acquired in 2014. Today, less than 1% of land that the A.T. traverses is privately owned.

Giving Back and Getting Involved

Because the ATC has played such a major role in land-acquisition projects as well as protecting, promoting and managing the Trail, the group reorganized and officially changed the name to Appalachian Trail Conservancy in 2005 – a name that better represented its leadership in making the trail what it is today. In 2015, they celebrated their 90th year of protecting and preserving the Trail.

Although the ATC helps spearhead Trail management efforts, they rely heavily on communities and volunteers to help. With more than 2,000 miles to maintain, there are plenty of opportunities to get involved and give back. Volunteers can join one of 31 Trail Clubs that assist with on-the-ground stewardship with the ATC coordinating efforts to:

- Keep footpaths passable

- Make sure surrounding land is protected

- Watch out for invasive species

- Get involved in the A.T. Community Program

- Participate in trail management efforts

Although government agencies helped make the land public, volunteers are the driving force that help keep the A.T. open for all to enjoy. Trail Crews typically work from May through October with projects available for all skill-levels.

While the path to preservation hasn’t always been a straightforward one, conservation of the A.T. has mostly been a cooperative effort over the years. From government agencies to private citizens, it takes a lot of work to maintain, promote, and protect the Appalachian Trail.